Singing Bill Withers on Father's Day Morning

and the politics of holding people to your chest when they need it

It’s Father’s Day morning, so I did what I do every day of my life. I put on some music and made breakfast for my family. On Sundays, I tend toward old soul or R&B stuff: Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, Jackie Wilson, the Temptations. Today I went with Bill Withers’ album Just as I Am. The second track, “Ain’t No Sunshine” is one of my all-time favorites.

The song always reminds me of when my son was little - about a year old - and he would cry so deeply when my wife left. I’d put on this track and hold him against my chest and sing it into his hair while we danced. He would still cry for about 2/3 of the song, but by the end, he’d be ok. We’d get on to our day of minor adventures.

I knew he’d prefer to have his mom around, but there wasn’t anything I could do about that. What I could do was love him and give what I always have on hand, which is some music and my body. It didn’t fix things, but it gave him a chance to move through his sad times and get to the other side. And I’m pretty sure he understood it that way, even though he was so little, because there was this melancholy afternoon a bit later on when he was probably about 2. I was standing at the sink doing dishes in our tiny apartment and I was singing “Ain’t No Sunshine” to myself when I felt him wrap his little arms around my leg and lay his face against me. I looked down to see if there was something wrong. But he was looking back up at me with this particular face he gets - a pair of serious eyes and a huge smile, combo of concern and determination to cheer. He’s a lover, that one.

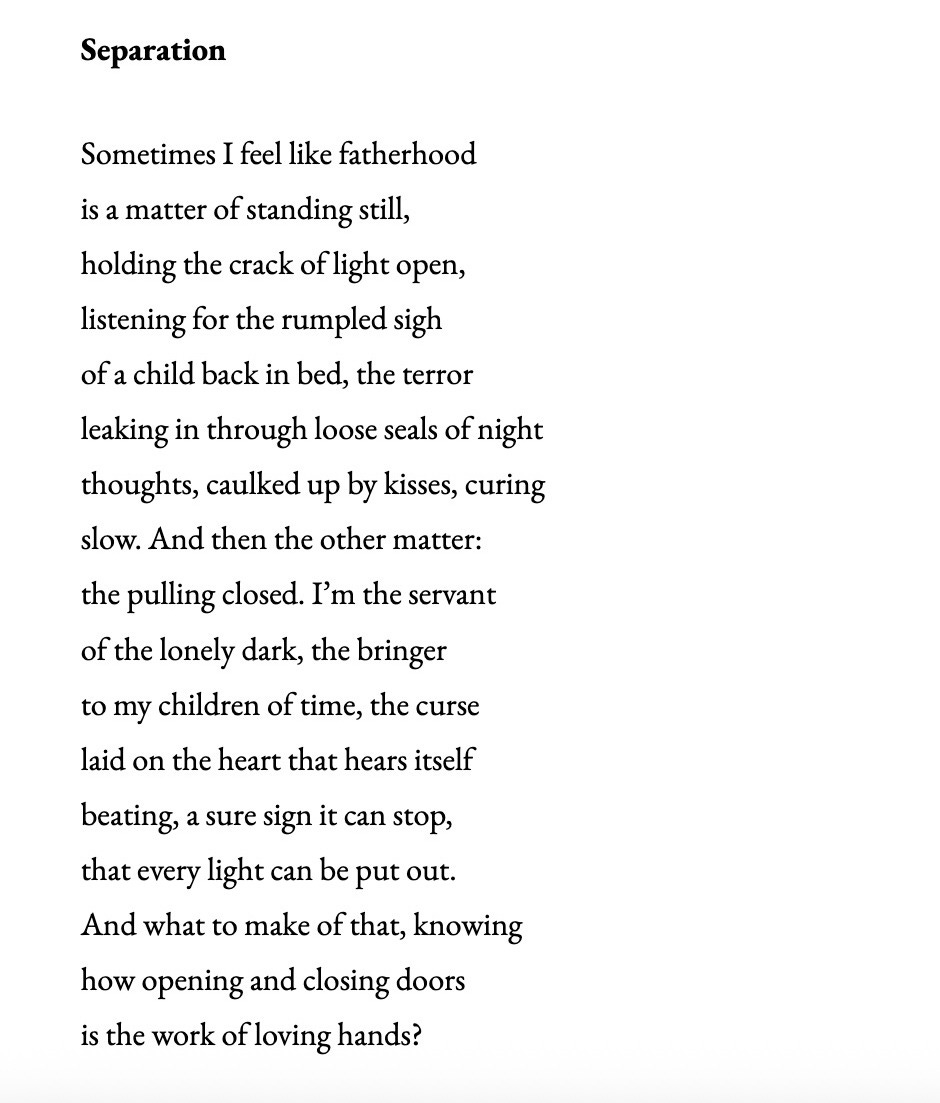

In a lot of ways, that’s what I think parenting is - the setting up of possibility for someone to find their way to happiness or whatever else it is they need. It’s not heroics. It’s a support role. And sometimes, as part of the process, it involves being a bit of a midwife of discomfort along the way. I wrote about that in a piece I published recently in One Art.

I can’t do anything about the existential terrors that come on in the middle of the night, besides hold my kids against my chest and rumble a song before sending them back to bed. That feels unsatisfying sometimes - even paradoxical - because the more love I give them, the more likely they’ll feel the sting of late-night mortality. Still, they work through it, and I have to figure that they’re better off for having been kissed in the middle of it. How could they not be?

If this is what being a dad is - not a protector in the righteous masculine violence kind of way or a unilateral problem solver in the domineering sense of the old patriarchal dad that I’ve tried so hard to avoid (though, of course, my scars are as deep as anyone else’s on that score), but someone standing back until a moment of soothing is necessary.

And I’m wondering how that prompts me to see this political moment and my role in it a bit differently. I have absolutely no power to put out the fires that are eating up the world. But I have care. I have food for people who don’t have enough food and I have time to sit with students who need to figure out how to keep their shit together and I have plants growing in my yard that take down a bit of the angry redness of stings and bites. I can stand outside of courthouses so the people trapped inside feel just a touch less alone. I have the time to write things that absolutely will not break through the barricades around fascist hearts but might provide some decent person with a bit of reassurance or perspective while they figure out how to do what they can right now too.

Don’t get me wrong. Thinking about myself in a support role like this doesn’t rule out the other things - the bodily defense of people who need it, the fierce engagement with the evils fucking up everything everywhere, the active argument against fascists at home and at large - but it kind of re-orients me when I’m figuring out what’s the most productive way I can be in the world and how I can help set up the conditions so we can find solutions.

Of course, that seems really abstract. And I’m ok with that. I’m trying to figure out how “doing not doing” can be as radical as I know it is. That’s important.

On the other hand, there’s this concrete shift in material reality that comes along with this idea too. Because I agreed with my son in those early days. It’s unspeakably sad to be separated from the people you love. But the ravages of capitalism require us to sell our days cheap for just a few minutes of time together. There wasn’t anything I could do about that except comfort him through it. But fast-forward a dozen years and what does he see? My wife and I, back together and on the porch or at the table by 3 most days. We don’t have much money, but we’re together a lot - way more than other families. As a small business owner, she rejects the coercive laws of competition that suggest she has to put 80 hours a week into endless growth and accumulation. As a teacher, I ignored the better-money tenure track path so I could focus on my students and writing in ways that bend organically around our needs as a family and our desires to be able to show up for community at short notice.

We’re fortunate as shit for sure, but it’s also taken a bit of imagination and rejection of the wide gate and broad road of capitalist solutions. So, while togetherness was a source of comfort and loving support, it also provided a touch of an alternative to capitalist interactions. That feels like something to build on, right?